December 19, 2021, 10:00 AM

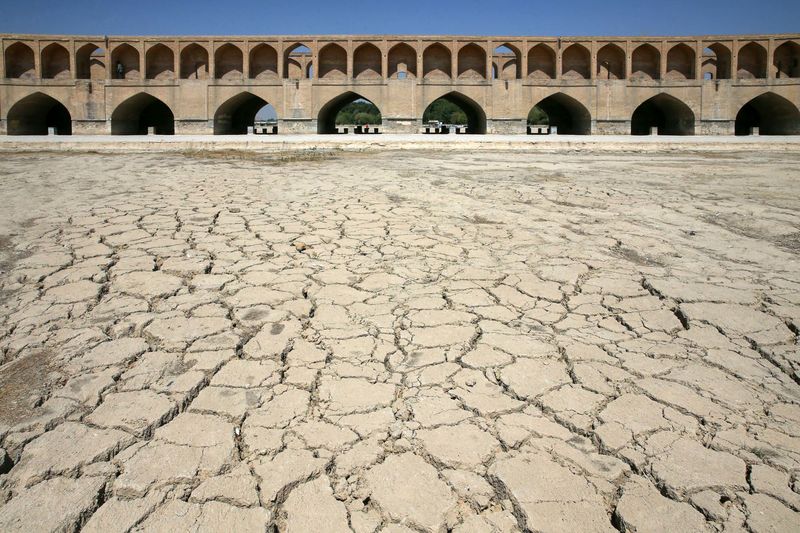

It was a gushing river that turned the ancient town of Esfahan into a cultural paragon that twice served as capital of the Persian Empire. But today, as it trickles through Iran, the Zayandeh Rud is a dried up battleground.

Thousands of Iranians flooded the barren riverbed last month to protest against the state’s management of water resources during the worst drought in decades. Social media videos showed baton-wielding security forces step in to quell the crowd, leaving some with bloodied faces, including a middle-aged woman cloaked in a black chador.

Deadly clashes also took place this summer in the province of Khuzestan, 180 miles away, where decades of oil exploitation has drained wetlands and destroyed once-fertile soil.

Iran’s Water Crisis

Shortages have destroyed farms and limited drinking water in affected cities and provinces

As Iran’s conflict with the U.S. intensifies, frustrations have grown over how the country’s leaders have reacted to crippling sanctions. Public support is at a record low, in part because of crackdowns on dissent. Now a long-brewing crisis over water scarcity, the result of decades of unchecked industrial expansion, poses a challenge that could eclipse Tehran’s fight with Washington over how to revive the 2015 nuclear deal.

“Our drinking water is getting worse and the farmers are losing their livelihoods,” says Tahereh, an environmental activist who participated in the Esfahan protests and asked not to use her full name for fear of reprisal. “I can’t forget the smell of the breeze that used to lift off the river when I walked to school as a child. Now I can only sense and feel it in my dreams.”

Climate change is exposing the weaknesses of an economy built on oil extraction and unsustainable agricultural practices. As the planet gets hotter through mid-century, Iran is likely to experience more extended periods of extreme high temperatures as well as more frequent dry periods and floods, according to a 2019 study.

This is true of many places, but the impact will be particularly acute in Iran: “Without thoughtful adaptability measures,” the researchers wrote, “some parts of the country may face limited habitability in the future.”

Many dams registered record levels of evaporation this year, triggering power outages at the height of one of the hottest summers ever recorded. The snowfall that accounts for 70% of the water in the Zayandeh Rud dropped almost 14% between 2017 and 2020.

The changing climate is exacerbating the consequences of earlier government decisions. Lobbying by local politicians after the revolution turned Esfahan into a major hub for steel-making, increasing pollution and straining its water resources. Then the Zayandeh Rud’s water started disappearing two decades ago after engineers diverted its flows to support industrial plants outside another desert city.

Even as supplies dwindle, Iranians who can access water continue to over-consume. A resident of Tehran uses three times more water than a person in Hamburg, Germany. Even in the midst of drought, gardens, public parks and landscaping in Iran’s capital remain well-watered. It’s common practice to spray pavements to cool them down.

People have also taken to illegally digging wells to scavenge what water they can, even as more legal wells spring up on approved land. Farmers in Esfahan have dug more than 10,000 illegal wells in recent years, a former official from its regional state-run water company told state-run Islamic Republic News Agency.

But implementing policies to ration water and halt the unlawful digging risks sparking further unrest, says Susanne Schmeier, an associate professor of water law and diplomacy at the IHE Delft Institute for Water Education in the Netherlands. “There are 130,000 illegal wells that are known of but there is no effort to plug them,” she says. “The question is, what are the alternatives and what are the social implications?”

In a televised interview on Dec. 5, President Ebrahim Raisi acknowledged the water crisis and said officials had been instructed to ”get to the heart of the problem and work on it.” Several government commissions have been established. “Alongside prayers, we also have to make and implement plans,” Raisi said. “There are problems but there are also solutions — we’re not at a dead end.” The government hasn’t yet published any detailed plans.

Soheil Sharif, a pistachio farmer in the central Kerman province, traces the roots of the crisis back to policies implemented after the 1979 Islamic Revolution. Newly isolated from the West and facing invasion by Iraq, Iran’s new clerical leadership wanted self-sufficiency and food security. They encouraged rural families to start farming, providing them with heavily subsidized water. A dam-building spree followed.

“The new leaders said the U.S. wanted to make us dependent on their wheat imports and they told everyone they could dig wells,” Sharif says. He estimates that 95% of the more than 1,000 wells in his neighborhood were dug with government permission, regardless of their location or impact on water resources.

“The problem is fundamentally about how the economy is managed,” Sharif says. “You can’t encourage people to look at water as this big pool that’s there for everyone to use and then tell them they have to treat it like a precious resource.”

Facing criticism of its water policies, Iran’s leadership has a familiar response: Blame it on the U.S. sanctions.

At the COP26 climate summit in Glasgow, Ali Salajeghe, vice president for environmental affairs, argued that restrictions have prevented Iran from taking steps to protect the environment. The government has said it will cut emissions 4% by 2030 from “business as usual” — a goal that actually translates to a quintupling from 1990s levels — and could target a 12% reduction if penalties are lifted.

Yet whenever sanctions have eased, such as in 2016, policy makers have focused on modernizing the oil industry as the fastest way to shore up growth. In times of economic strife, one of the easiest ways to avoid unrest is to generate jobs by launching big infrastructure projects, such as dams and refineries. But the costs of that “resistance economy” approach have often been borne by citizens who are losing patience, especially those in impoverished border regions who have been traditionally marginalized because of their ethnicity or religion.

“By prioritizing accelerated development, partly to prove defiance to Western coercion and with self-sufficiency as a regime objective, Iran resorted to high resource use to sustain its diminishing economy,” says Shirin Hakim, a researcher at the Centre for Environment Policy at London’s Imperial College. “Sanctions cannot be blamed for this outcome, but it is evident that they have acted as a catalyst in inducing managerial difficulties.”

The former deputy head of Iran’s Department of Environment, who served under moderate former President Hassan Rouhani, recalls a model he developed while studying in Sweden in 2005. It was built to assess potential solutions to alleviate the river’s dryness and showed that even diverting water from neighboring provinces wouldn’t help.

“It was shocking to me,” he says. “I ran the model many times thinking there was a mistake until I realized that more water supply will promote further growth,” increasing demand and creating “a vicious cycle that will worsen the situation in the long run.”

No one listened. Madani left Iran in April 2018 after he was arrested several times by intelligence forces who were deeply suspicious of officials with foreign ties and Rouhani’s efforts to improve Iran’s relations with the West. They treated environmentalism — once a benign civil society cause — as something akin to a national security threat. Madani is now a research professor at City College of New York.

Other advocates have also come under pressure. In early 2018, nine environmentalists were arrested and charged with spying and violating national security — an accusation often levied against dual nationals or Iranians with personal links to the West. All of them have denied the charges. One of those detained, a prominent professor named Kavous Seyed Emami, died in jail. Iran’s judiciary said he committed suicide. His family have strongly rejected the claim.

Ayoub, a 30-year-old activist from Khuzestan, says water scarcity multiplies existing grievances. The oil-rich province was the site of the most violent crackdown in November 2019 as demonstrations swept through the country; protests still occur frequently. Residents of have long resented domestic and foreign powers who came to extract the crude hidden deep under their land. In the process, they destroyed marshlands and fertile soil, while excluding locals from the profits, Ayoub says. He declined to give his full name for fear of reprisal.

Ahmad Midari, Iran’s deputy welfare minister, concedes that there have been missteps. He told state television that the government made “big mistakes” because it wanted to develop cheaper onshore oil fields “with little concern for the environment.” He said local politicians would acquire permits from the Department of the Environment in Tehran through lobbying and nepotism so that they could drain large sections of the Hoor al-Azim wetland in order to dig oil wells.

Iran’s water stores may never be refilled. The country needs to overhaul not just its water management policies but the economy as a whole, says Madani. He says the government should invest in jobs that will give farming communities effective alternatives, raise awareness about environmental challenges and substantially modernize the agricultural sector.

Iran is “in denial,” he says. “It keeps thinking it can mitigate or spend its way out of the problem instead of adapting.”