By Hamid Yazdan Panah

This summer marks the 26th anniversary of Iran’s massacre against political prisoners in 1988. The shock and terror inflicted on the Iranian nation when tens of thousands of prisoners were executed in a matter of months went unnoticed in the international sphere, and unresolved in the Iranian psyche. The legacy of this event has resulted in the survival of a despotic regime, and the stunted growth of a nation.

A Decade of Blood

In order to understand the effect of the 1988 massacre, it is necessary to situate it in the historical context of 1980’s Iran. A decade which had started out with the highest of aspirations following the 1979 revolution, turned into a nightmare of horror and tragedy. The war with Iraq which started in 1980 also was used by the Mullahs to suppress criticism and justify their expansion of power. Khomeini entered Iran with religious sanctity that was unparalleled, his betrayal of the peoples trusts has instilled a cynicism towards politics in Iranians that continues to this day.

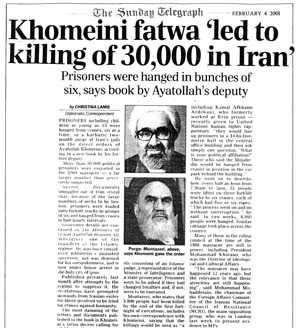

The massacre itself has never been formally investigated, and remains shrouded in mystery. Some estimates place the number of killed as high as 30,000. To date, the most damning evidence has come from within the ruling clergy itself, from Grand Ayatollah Hossein-Ali Montazeri who lost his status as Khomeini’s successor by denouncing the massacre.

The orders for the systematic execution of dissidents came from Khomeini himself, in the form of a fatwa (religious edict) and was meant to purge the country of any opposition, notably the People’s Mojahedin Organization of Iran (PMOI) who represented the largest threat to ruling clerics. Along with the PMOI many leftist activists were also executed, for refusing to renounce their beliefs. A large number of the prisoners who were executed had already been sentenced to serve a number of years for their crimes. Their executions occurred with little regard for due process or judicial oversight.

“My brother was killed on 28 August. In late November the authorities called us… they said that both my brothers had been executed but they didn’t give any documents. They didn’t say why they killed them, where they had been buried, why there had been a re-trial, their last words, nothing,” Jafar Behkish told Amnesty International.

For a complete legal analysis of the massacre and evidence of crimes against humanity see this Report by Geoffrey Robertson

According to testimony given to United Nations human rights rapporteurs Kamal Afkhami Ardekani, who formerly worked at Evin prison: “They would line up prisoners in a 14-by-five-metre hall in the central office building and then ask simply one question, ‘What is your political affiliation?’ Those who said the Mojahedin would be hanged from cranes in position in the car park behind the building.”

Amnesty International has noted that 25 years after the massacre, the regime continues to suppress any information

The effects of Trauma

Much has been written about the horrors of the massacre and what occurred, and there exist numerous eyewitness accounts. That which is not often discussed is the affect the massacre had on the nation as a whole.

First and foremost the shock of such a brutal and systematic massacre left the country paralyzed with horror. Unable to comprehend the extent of the tragedy, many denied that it had even taken place. Others were left in a state of shock, unable to demand an investigation, or properly mourn and move on.

The trauma has been passed on to the younger generation as well. Children who grew up in this era were caught between a bloody war, and the horrors of the government. Some would hear about the execution of their relatives from neighbors or classmates, because their own families were too afraid to share the news.

Some families are unable to accept the truth of what has occurred to this day. An elderly couple still hold hope that their son somehow escaped prison and has been in hiding for 26 years. This type of wishful thinking is indicative of the deep seated trauma inflicted on the nation that has been unable to move on from the Khomeini’s betrayal of their hopes and aspirations.

As a result, to this day many Iranians eschew political involvement of any sort, and maintain extremely cynical views. Some, including many in the West, have simply blocked out the horror of such events, and live in a state of denial. They ignore any sense of responsibility towards the massacre or the inequalities of Iran as a whole.

The second major effect of the massacre was growth of a particular viewpoint among Iranians in regards to

This mode of thinking legitimizes the regimes power as an accepted fact and life, to be feared and ultimately respected. As a result if an individual is detained, hurt, or killed by this power than it is the individuals own choices which were wrong.

A compelling example of this is offered by a number of Iranians who claim to be “reformists” and their coverage of the 2009 uprising in Iran. For the first time since the 1980’s, Iranians took a bold stance calling for a complete end of the regime. The world witnessed scenes of graphic violence against unarmed protesters, yet instead of condemning the regimes barbaric acts, these Iranians continuously claimed that the PMOI were to blame for “provoking” the regime into violence. It is no surprise that the regime itself continues to use such arguments to this day, even in regards to the killing of Neda Agha Soltan.

Others have sought to omit the PMOI entirely from their coverage of the massacre, and while acknowledging the massacre they ignore the political context, and rob the prisoners of the very thing which they died for. By continuing this culture of victim blaming, Iranians have stifled their own ability to form coherent resistance to the regime, and a united opposition. Instead individuals are encouraged to shun politics, focus on their personal life and keep their mouths shut lest they bring misery upon themselves.

The massacre in the 1980’s served the regimes short term and long term interests of legitimization and survival through violence and terror. This policy has continued to this day. It is not a coincidence than that Iran continues to execute individuals in public, and leads the world in per capita executions.

Moving Forward

Sadly, for many Iranians it is as if they are hoping to wake up from a nightmare, and that just maybe they can

It is time to accept the truth of what occurred in Iran, and resolve to move forward. Only by accepting death can we move on from it. Those that had the courage to stand up to the regime in the most horrific conditions should be remembered as heroes, and their legacy should inspire us to remain steadfast in our resistance. The culpability for this tragedy is squarely with the regime, and Iranians should demand an investigation by the United Nations into what amounts to crimes against humanity.

Hamid Yazdan Panah is an attorney and human rights activist from the San Francisco Bay Area.